|

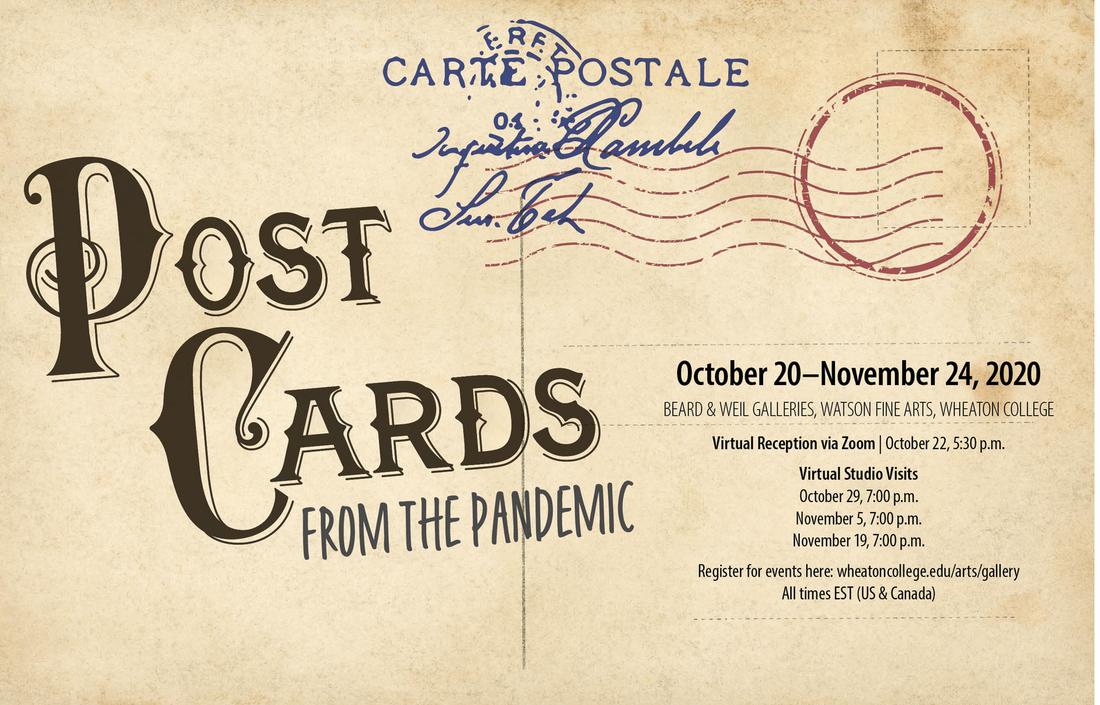

From the galleries' site: "This exhibition is an open call for postcard-sized responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. All submissions will be included in the exhibition and become part of the Wheaton College Permanent Collection. The exhibition is an effort to combat the social isolation this virus has forced on us. It is a chance to see, through the eyes of another, an expression of this experience. It is an opportunity to come together when we still have to remain physically apart." I was fortunate to be invited to submit to this show. They requested pieces no bigger than 5" x 7" (postcards!) of the work you've been doing during the pandemic. The postcards will become part of Wheaton College's permanent collection. While the exhibition emphasizes the results, the expressions, of artists' response to the pandemic, for me the process of getting there was just as important. At the start of the pandemic and the subsequent quarantine I, like many people I know, were able to look ahead and see that for scientific and political reasons, what was just beginning would be with us for a very long time. With that understanding I settled in for the long haul and took the opportunity to begin something that I had been dreaming of doing for quite a while: Go back into the studio (though in my case the studio is a table in the sun on my porch during good weather, or my kitchen table lined with old cardboard when it's not.) I will admit that for years I was frozen by a very silly but real fear of failure from attempting this, but the pandemic with its sights set directly on our mortality quickly overrode my fear. It was now or never. If ever I were to start drawing and painting--no! check that, for it was the classical definitions of drawing and painting and art that had frightened and deterred me as much as the embarrassment I thought I'd feel from friends who are very accomplished artists-- if I were going to start making art pieces--what I define as something that didn't exist yesterday--then now was the time to do it. I've always defined myself as a writer and an artist, and being an artist I would then say, I am an artist who primarily makes images (photography) or I am an artist who works in the theater. But the artist part always came first. I'm seeing on Facebook that a lot of my peers in the theater seem to be suffering more than others during the disturbances brought on by the pandemic because theater is all they know how to do. They write, it--acting, directing, scenic design, whatever the discipline--is something they trained their whole life for and now that the theaters are shut down they don't know what to do. As much as I love theater--and I do love it deeply and I did study it and paid a lot of money to a university to learn about it and devoted a lot of my life to it--the artist in me always found it restrictive because, if you were a playwright like I am, you really are not only not expected to be able to design a set, you're pretty much denied it. With any other artistic pursuit there's not just the expectation but almost a requirement that you'll explore other mediums. When funding for my theater went away, admittedly I was disappointed at first, but then shrugged and figured out something else to do. You really can't keep a creative person down; they will always find an outlet. As much as I love making theater, and as much as I love making images, right now I'm loving smearing and scratching and spreading paint. Like Hemingway tried to write one perfect sentence in a day, right now I'm just trying to make one perfect mark. You can love all of your children, you don't have to have a favorite. I'm not going to get into the steps of how I reentered the studio, how I replicated my old palette, bought former favorite art supplies like an enamel butcher pan or a collection of palette knives whose handles are already getting worn and paint-spattered. What became most important to me was suddenly how free I felt to do whatever I wanted, regardless of what the established art community might think. Don't even ask me what the "established art community" is or who composes it. I imagine in my mind they're all the gallerists and curators who'll I'll bump heads with later when I try to exhibit or sell some of this stuff. I used, and continue to use, tools I dug out of my toolbox like plumb lines, squares, and carpentry pencils. Right now some favorite tools are scrapers for stenciling I found on a pegboard in the painting department of a Home Depot. I use an old mat knife to scrape children's blackboard chalk to make dust, and transfer paper, i.e. good old-fashioned carbon paper. In other words I'll use anything or do anything to get marks on paper (and while today it's paper, who knows what it might be tomorrow!) I addressed and continue to address whatever is in front of me. A loved one. A favorite painting (can you spot the Hockney somewhere on this site?) The pandemic. And while I'm still taking baby steps, I'm growing every day, developing a painting language and an eye and through that growth I'm still very much aware that I'm alive, which is a good thing to be during a pandemic. Here are the pieces I submitted:

0 Comments

It was a working title, I've since jettisoned it, because it's how I'm exploring memory. What does memory look like? But it's something in my head. I'm making marks with carpentry tools. T-squares and carpenter pencils. On a bigger piece I'll use a blue line; I'm anxious to see the chalk wisp along the line. I'm making lines like a child who thinks what he's doing is so important, so grand, but isn't. That's how I see America being made better right now. I like seeing lines dissolve, fade, into dust. Even real dust from pastels.

I love process. I love reading about other artists' process. How did you do that? Today I read about an artist who just won a big prize who fills maybe three sketchbooks before she starts a painting. But then the painting doesn't change. I'm not so capable. Today, I tore three pages out of a sketchbook, and then took a nap. When I woke, I filled the three. That's all. The last three above. The ones with color. I want to learn how I feel about these lines. I want to understand what they are capable of doing. I have a little Fujifilm point-and-shoot that I bought while I was traveling in Canada when I once again had broken I think it was my third Nikon Coolpix. It's shock and water resistant and I carry it just about all the time. It's my little friend, my little sketchpad, and what I like most about it is I never know exactly what it's going to do. It gives me a lot of control, but many times it, well, it doesn't take over, but it's almost as if it says, wait a minute, why don't you look at it this way? It's still during the pandemic, when it seems it's still going to to be a year or more when I'm trapped in my apartment, on my porch, in my garden, when I'm almost too frightened to walk to the post office. When you jack the ISO all the way to 3200, the results look like charcoal drawings. These images of garlic sprouts were taken with a simple USB microscope my marine biology daughter, knowing my love of image making and nature, gave to me as a gift off Amazon. I think it cost about twenty dollars. There is a focus, and that's about it, that's about as sophisticated as the technical control gets that I have at my disposal. The image capture-er--I hesitate to call it a camera or even a microscope though we really are capturing light--records the light in jpegs at 72 dpi, and I control the lighting the best I can by paying attention to the background that is reflecting light back into the scene and the ambient light. I print these images small, 5 x 3 inches, centered on bright white pieces of vertical washi paper. That's it for all of us who like to geek out on technology and process. But...but, it takes an artist's eye and it takes curiosity to be making dinner and see this very tiny green slip nosing out of onion skin on the cutting board. And it take curiosity to wonder, what does it really look like in its own Lilliputian world? And perhaps you might think it's arrogant to say, but it takes an artist's eye and control to see a fleeting image (because hand-holding the mechanism at 500x or 800x and certainly at 1000x only intensifies camera shake) and compose it, and take the image. If you look at these images and think, well, my three-year-old could have done that, I guess all I can say is, Thank you, I've done my job. But I've also done my job as an artist if, when you see these images, you pause and wonder at the beauty of the world around us, and it makes you ask yourself, what else am I missing? And how do I make myself see it? |

Author

John Greiner-Ferris is a politically motivated, multi-disciplinary artist in the Boston area. Sometimes he makes images. Sometimes he writes. Sometimes he does both. Archives

May 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed